On March 16, 1935 Germany rolled out the Wehrmacht, a brand-new unified armed force that replaced the old Reichswehr. Just a few months later, on June 1, the former Reichsheer was officially rebranded as the Heer, the army branch of the Wehrmacht. The shake-up also brought in the Luftwaffe to handle air power and the Kriegsmarine for naval operations. Strategic control over all three branches sat with the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), the high command.

Combat History of the Wehrmacht in World War II

Before World War II began, the Wehrmacht gained its first combat experience in the Spanish Civil War. Starting in 1936, Germany supported General Franco by sending the Condor Legion—over 5,000 troops along with aircraft, tanks, artillery, and instructors. The deployment served as a proving ground for new equipment, officer training, and inter-service cooperation.

In March 1938 the Wehrmacht marched unopposed into Austria, an event remembered as the Anschluss. A few months later, after the Munich Agreement, Germany secured the Sudetenland, a German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia. By spring 1939 German troops occupied the rest of Czech territory, establishing the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. These bloodless gains soon gave way to real war.

On September 1, 1939 the Wehrmacht launched a full-scale invasion of Poland. Within weeks Soviet forces entered from the east, and the campaign ended in less than a month—Poland was partitioned between the two powers. Britain and France declared war on Germany.

Germany next turned north. In April 1940 it occupied Denmark and attacked Norway, clashing with Western Allied troops for the first time. In May a lightning campaign swept through Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg before driving into France. The French defenses collapsed, and on June 22 France capitulated. Italy had already joined the war on Germany’s side.

After the swift victory in the West, German strategy shifted to Britain. During the summer of 1940 the Luftwaffe—reinforced by Italian aircraft—mounted daily mass raids aimed at destroying the Royal Air Force. The RAF held out, forcing Germany to cancel its invasion plans—Germany’s first major setback.

Early in 1941 attention moved south. In February the Afrika Korps under Erwin Rommel arrived in Libya to bolster struggling Italian forces. A rapid counter-offensive pushed the British back to the Egyptian frontier and stabilized the front.

Spring 1941 also saw the Balkan campaign. In April the Wehrmacht invaded Yugoslavia after a coup overturned its Axis alignment; the country fell within days. German forces then struck Greece, where Allied troops tried in vain to hold them. In May German paratroopers seized Crete—the first large-scale airborne assault in history. Heavy losses ended German ambitions for further mass parachute operations, yet Allied planners later drew on those lessons for Market Garden in 1944 and the D-Day landings in Normandy.

On June 22, 1941 Germany opened a vast new front by invading the Soviet Union. The offensive stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, overrunning the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine, and reaching the outskirts of Moscow before stalling that winter. In 1942 the focus shifted south toward the Volga; the Battle of Stalingrad ended with the encirclement and surrender of Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army—a decisive turning point.

Late 1942 brought setbacks in Africa as well. Defeat at El Alamein forced a retreat, and in May 1943 Axis forces surrendered in Tunisia. The Allies landed on Sicily, then on mainland Italy, launching the Italian campaign. On June 6, 1944 Western Allies opened a second front with the Normandy landings, liberating France and Belgium while the Red Army advanced from the east.

By early 1945 Allied armies closed in on Germany. In April Soviet troops stormed Berlin; after fierce street fighting the capital fell, and on May 8 Nazi Germany surrendered. The Wehrmacht was dissolved, and that autumn the Allies formally disbanded the remaining German armed forces. A decade later the new democratic West Germany was permitted to raise a modern army—the Bundeswehr.

Evolution of Wehrmacht Vehicle Camouflage

Throughout World War II, the Wehrmacht’s paint schemes underwent several major overhauls, driven by changes in strategy and the terrain where the fighting took place.

At first, combat vehicles retained the three-color Buntfarbenanstrich (three-color camouflage) inherited from the Reichswehr, while non-combat vehicles stayed in plain Feldgrau (field gray).

In 1937 a new standard appeared: a dark-gray base mottled with dark-brown patches. Official manuals listed it as Gerätanstrich dunkelgrau/dunkelbraun (dark-gray/dark-brown equipment finish), also called the neuer Buntfarbenanstrich (new multicolor camouflage). By the summer of 1940 the brown was dropped, and vehicles were painted overall in Dunkelgrau (dark gray).

Each winter, crews whitewashed their vehicles with a washable chalk-based white paint that either wore off naturally or was scrubbed away in spring.

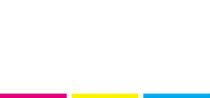

The North African campaign demanded a fresh approach. In March 1941 the Army High Command (OKH) introduced a two-tone desert scheme—Gelbbraun (yellow-brown) over Grau (sand gray)—applied on top of the regular European gray. A year later, in March 1942, both colors were replaced with new desert tones.

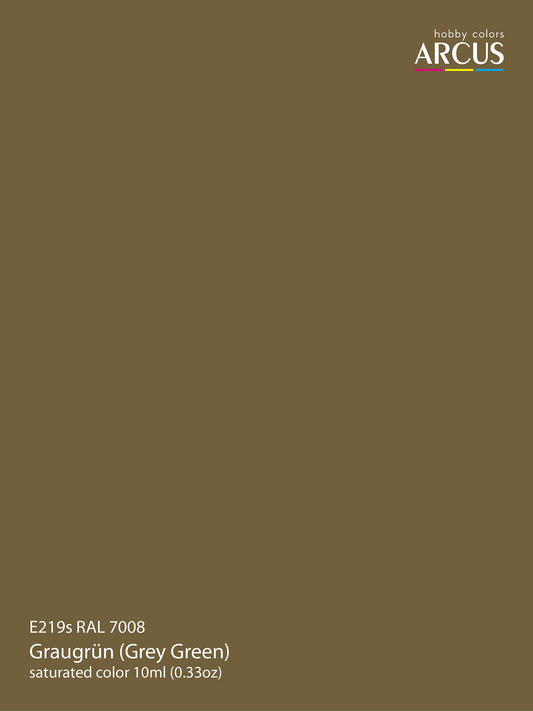

Back in Europe, Dunkelgrau proved too conspicuous on the wide-open Eastern Front. In the spring of 1943 the base coat switched to Dunkelgelb (dark yellow), and factories began shipping thick paint concentrates so field units could add Rotbraun (reddish brown) and Olivgrün (olive green) patches in the field, a system known as Tarnanstriche.

By early 1945 paint and solvents were scarce. The army adopted the Sparanstrich (economy finish): the same three colors were sprayed directly onto the primer, skipping a full base coat. The base shade also flipped—olive green became the starting layer instead of dark yellow. In the war’s final weeks many components left factories wearing only red-brown primer.

German Army Color Standards in World War II

Years before the Wehrmacht existed, German engineers were already working to standardize the paint palette. In 1927 the Reichs-Ausschuss für Lieferbedingungen (Imperial Supply Committee) issued a 40-color chart known as RAL 840; that civilian reference later formed the backbone of military color standards.

Up to 1941 armor paints were identified only by a name and serial number—Grün Nr. 28 (Green No. 28), Schwarz Nr. 5 (Black No. 5), and so on. Because these labels lacked fixed reference chips, factories often produced slightly different shades—acceptable in peacetime but problematic once wartime mass production began.

On 10 February 1941 the Wehrmacht overhauled the system: every color received a four-digit RAL index instead of the old names and numbers. Dunkelgrau Nr. 46 became RAL 7021 Dunkelgrau, Grün Nr. 28 turned into RAL 6007 Grün, and so forth. Tying each hue to a single master sample streamlined procurement and gave the entire force a common color language. The RAL system remains widely used today in both military and civilian industries.